Can the Transorbital Endoscopic Approach Replace Craniotomy or Transnasal Surgery?

— A Case for Coexistence, Not Competition, in Skull Base Neurosurgery —

Introduction

With the advancement of endoscopic technology, neurosurgery has seen a steady expansion in minimally invasive options. One such technique gaining attention is the transorbital endoscopic approach (TEA).

However, skepticism remains. Many neurosurgeons question its necessity, arguing that traditional craniotomy or transnasal endoscopic approaches are sufficient for most skull base lesions.

In this article, we explore the clinical utility, anatomical basis, and complication profile of TEA, drawing on insights from the systematic review by Vural et al. (2021). We particularly address how TEA can coexist with—and complement—conventional approaches.

Key Findings from Vural et al., 2021

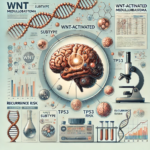

This comprehensive study reviewed 42 clinical publications and 193 patient cases, combined with cadaveric dissections on 4 specimens. It highlights:

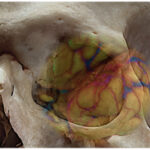

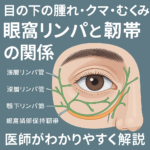

- The division of the orbit into four quadrants, each with a corresponding transorbital route (SLC, PC, LRC, PS).

- Key bony landmarks (e.g., SOF, IOF, GSW) for safe surgical navigation.

- An overall postoperative CSF leak rate of 4.1%, with most complications being transient or minor (e.g., diplopia, palpebral edema).

- Multilayer reconstruction was commonly employed, supported naturally by orbital contents.

These findings support TEA as a safe and feasible route for select anterior and middle skull base pathologies, particularly those located laterally.

TEA Is Not a Replacement — It’s a Complementary Tool

Vural et al. emphasize a crucial point:

TEA should not replace craniotomy or transnasal approaches—it should complement them.

Not all lesions are suitable for TEA, but in select cases, it provides a shorter, less invasive pathway, especially for lateral skull base regions that are difficult to reach via traditional routes.

| Lesion Location | Preferred Approach |

|---|---|

| Midline skull base (sella, cribriform plate) | Transnasal endoscopy |

| Lateral anterior/middle cranial fossa, orbital apex | Transorbital endoscopy |

| Extensive or deep lesions | Craniotomy |

Addressing the Skeptics: Why Should Neurosurgeons Learn TEA?

Common objections include:

- “The working corridor is too narrow.”

- “Craniotomy gives a full view.”

- “Orbital surgery risks vision and cosmesis.”

These concerns are valid, but the data from Vural et al. demonstrate that with proper anatomical understanding and reconstruction techniques, complication rates are low and outcomes are favorable.

Moreover, the orbital contents act as a natural buttress to secure grafts and reduce CSF leak risk. Cosmetically, TEA is almost scarless—an increasingly important consideration in modern surgery.

Conclusion: Expanding the Neurosurgical Toolbox

TEA is not a universal solution, nor is it meant to be. But in carefully selected cases, it provides unique advantages. It expands the neurosurgeon’s toolbox and offers an alternative corridor when traditional routes are suboptimal.

The coexistence of craniotomy, transnasal, and transorbital approaches allows for tailored, patient-specific strategies—and that is the direction modern neurosurgery must continue to move toward.

Reference

- Vural M, et al. Transorbital endoscopic approaches to the skull base: anatomical features, surgical indications, and clinical outcomes. A cadaveric study and systematic review. Neurosurgical Review. 2021.